SAEDNEWS: In Shakespeare's play "The Winter's Tale," he suggests that to have a second chance, we must let go of control and coercion over the world. In other words, we need to abandon the illusions of absolute power that we harbor as children.

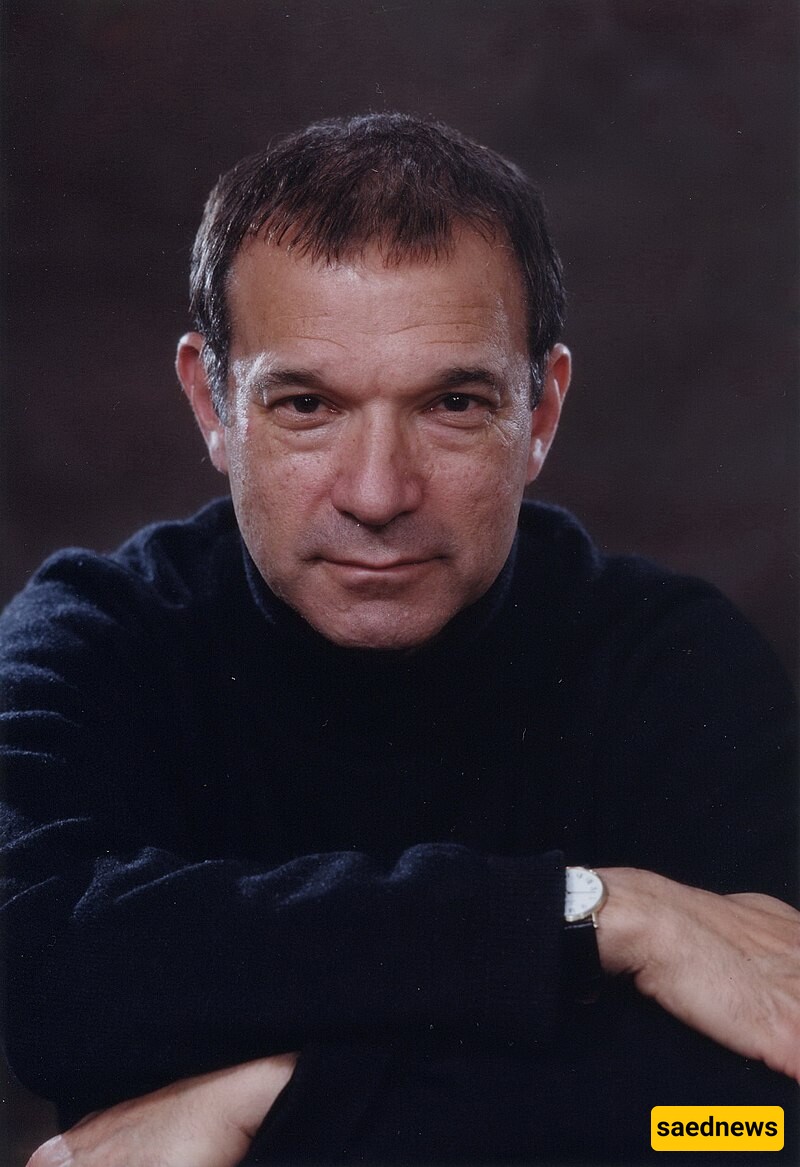

According to SAEDNEWS, Stephen Greenblatt is an American professor and author. He is regarded as one of the most influential Renaissance scholars in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Since 2000, he has been teaching as a Professor of Humanities at Harvard University. After 28 years of research and teaching in California, he moved to Massachusetts to work at Harvard.

Greenblatt is one of the founders of New Historicism, a collection of critical approaches he often refers to as "cultural poetics." He won the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction in 2012 and the National Book Award for Non-Fiction in 2011 for his book "The Swerve: How the World Became Modern." In subsequent years, Greenblatt authored several best-selling books on Shakespeare studies and Renaissance studies. Many of Greenblatt's books have been translated and published in Persian, including "The Swerve: How the World Became Modern" translated by Mehdi Nasrallahzadeh and published by Bidgol Publishing, and "Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics" translated by Abtin Golkar and published by Haman Publishing.

Many of us vaguely remember encountering Marx's observations about the repetition of history and his famous quote that history repeats itself first as tragedy and then as farce. Repetition can be futile, a shallow and artificial attempt to recreate what has been lost.

Marx was thinking about the extremely dreadful politics of France in the early to mid-19th century. However, this view applies to a wide range of political phenomena, such as various efforts to "reclaim sovereignty" or "make America great again" (Trump's slogan) or "restore the endless unity of the Russian world" (Putin's slogan). Listing these examples and considering what a second term for Donald Trump in the United States might mean reminds us that the farcical nature of the situation does not prevent a new wave of bloody disasters. The current tragedy may not be of the classic type, but the casualties remain high.

In our new book, "Second Chance: Shakespeare and Freud" (Yale University Press, May 2024), British psychotherapist Adam Phillips and I invite readers to look even further back to understand what causes tragedy. It seems that the answer for both Shakespeare and Freud is that tragedy occurs when we are left without the resources (internal or external) to reimagine what might be possible for us: the repetition of events with transformative changes.

We explain in our book how, as human agents, we start in a world of "first chances." These chances are hereditary and unplanned probabilities: where we find ourselves, who our parents are, and these factors occur before we are in a position to choose or understand what is happening to us.

The world of first chances is much more precarious than we initially thought: we are children playing on the edge of a cliff. Comedies work by depicting avoided risks, saved chances, and futures that are rescued from dissolution and disaster at the last moment. "The Comedy of Errors," with its absurd plot about twins separated in infancy who meet in situations that are both hilarious and highly dangerous, is an extreme example of this comic register where broken relationships are miraculously restored.

"A Midsummer Night's Dream," another comedy by Shakespeare, sets up a potentially deadly conflict and resolves it through a magical and theatrical sequence of betrayals, reversals, and emotional transformations. This is a process that in real life can be accompanied by deep pain and confusion, but here it is beautifully presented as a dream that can now be forgotten, returning everyone to where they truly wanted to be.

So, among many other things, Shakespeare's comedy offers a playful and insightful demonstration of what drama can achieve. His comedy can invite you to imagine disaster, fill it with various details, and then give way to an irresistible energy that aims for peace or a return to normalcy. By boldly imagining the worst and discovering resilience you didn't know you had, you learn to cope with instability. However, the price of this is denial.

Dreams must be forgotten, and the interim moments of horror and grief must be left behind. Shakespeare cannot be fully satisfied with this, and his comedies increasingly tend to give an unsettling voice to all these denied or suppressed elements (Malvolio in Twelfth Night is a clear example). Drama must do more, and tragic drama addresses risk and fear from a completely distinct perspective. In tragedy, you will actually lose your first chances and not regain them.

Then the question is, what can you hope for when you have failed, when you are hurt, and deeply damaged? The tragic hero is someone who fails to understand that they are no longer safe and innocent. These heroes must discover the realm of a great second chance, but for some reason, they cannot do so. A second chance is an ironic and self-aware moment when you see your failure as real and realize that you cannot simply escape it by starting over.

In our book, we note that almost all great tragedies contain a moment when the protagonist is offered a way out of the barren cycle of repetition in which they are trapped. However, these characters, with varying degrees of reflection and understanding, do not recognize or cannot grasp that chance. Therefore, at that moment, the only "second chance" for them is death.

In Shakespearean storytelling, the tragic narrative is not the final word, and his plays offer a bold possibility beyond the trajectory by refusing death. For example, in "The Winter's Tale," the tragic hero is given a second chance. In that story, Leontes is happily entertaining Polixenes, the King of Bohemia and his childhood friend. However, since he cannot convince his guest to stay for the entire winter, he asks his wife to insistently persuade him. When the queen easily secures the guest's agreement, Leontes' suspicion is aroused, and he imagines there must be something between them. This suspicion soon becomes his obsessive preoccupation, to the point where he orders one of his loyal advisors, Camillo, to poison Polixenes. But Camillo, who believes in Polixenes' innocence, warns him of the impending danger and helps arrange his midnight escape. Camillo himself also flees from the court of Sicily with Polixenes.

Shakespeare, in that play, suggests that to have a second chance, we must give up control and coercion over the world. In other words, we need to let go of the illusions of absolute power that we harbor as children.

In our book, Phillips points out that Freud identifies the greatest second chance in our lives: discovering that we can love someone other than our parents. However, the way this is done owes much to the brilliant narratives of British psychologist and theorist Donald Winnicott, who focused on early childhood experiences. In Winnicott's narrative, the second chance begins with a primary understanding of the child's relationship with the world, which is neither absolute control nor passive resignation. The mother must be sufficiently reliable so that the child does not feel abandoned forever.

Memory plays a crucial role in shaping a narrative where new challenges can be integrated into a pattern of letting go and recovery. Phillips mentions that the idea of a second chance is essentially the pure truth of learning. Our first experiences of desire and commitment must be reworked. This involves intense and painful changes, but it creates a story that, instead of looking passionately backward and making us immobile and passive, allows us to grow. That's why a second chance might not seem like good news to an injured and worried subject. Resistance to therapy runs deep (Freud wrote about how recovery is seen as a "new danger").

In our book, we ask what might be involved in choosing to be human: acting with open eyes within the limits we did not choose. By being prepared to see where we learned to harm and be harmed, we can review our behavior. Look around you: many of the moral and political horrors in our environment stem from fear of recovery, fear of second chances, unwillingness to learn, and a desperate look back to a time when we were powerful in our lives.

For Phillips and me, the temptation to return to a psychological world where there are still no limits to choice is a fundamental component of tragedy: Macbeth's terror of being seen, Cleopatra's fear in "Antony and Cleopatra" of being taken to Rome by Caesar Octavius who has defeated Antony before her suicide, Othello's pathetic efforts to salvage his narrative and reputation before his suicide, even Hamlet's insistence that Horatio stay alive to honestly tell the prince's story—all these point to the tragic compulsion to control or assimilate the threatening external world.

"The Comedy of Errors" is a play by Shakespeare, written around 1593-1594. It is based on the Latin comedy "Menaechmi" or "The Twins" by Plautus. The story involves twins who are unaware of each other’s existence and their accidental meeting results in a series of humorous and unfortunate events. The twins were separated at birth due to a storm at sea: the first pair are nobles, both named Antipholus, and the second pair are servants, both named Dromio. Years later, the first pair, having grown up in Syracuse, accidentally visit Ephesus where the second pair live, leading to confusion and comedic situations.

In "A Midsummer Night's Dream," Theseus, Duke of Athens, plans to marry Hippolyta, and orders a celebration. However, not all young Athenians are happy about this. Lysander and Demetrius, friends since childhood, are both in love with Hermia, and her father demands that she marry Demetrius. If she refuses, she faces death or life in a nunnery. However, everyone knows Hermia loves Lysander.

"Twelfth Night" is a comedy by Shakespeare, written around 1599-1601 and first performed on February 2, 1602. It explores themes of love and power. Lady Olivia is the object of Duke Orsino's affections, but she has other suitors, including her pretentious servant Malvolio and Sir Andrew Aguecheek. The story also involves twins Viola and Sebastian, who believe each other to be dead after a shipwreck. Viola disguises herself as a boy and becomes a servant to Duke Orsino, who sends her to court Olivia on his behalf. Olivia falls in love with Viola, unaware she is a woman.

"Twelfth Night" is one of Shakespeare's most entertaining plays. Malvolio, an initially annoying character, becomes more sympathetic as others bully him, highlighting how class and family can limit individuals' happiness and opportunities.